Why the love affair with man-eating plants?

Triffids from the BBC's 1981 adaption

By Finlo Rohrer

BBC News Magazine

A new BBC adaptation is being made of The Day of the Triffids, but why are we still prepared to believe in a post-apocalyptic world roamed by flesh-eating semi-sentient plants? And do we have a love affair with fictionalised destruction?

Picture the scene. Something bad has happened. Very bad. The streets are deserted. The people are either dead or fled.

The cause could be a natural disaster - a volcano, a tsunami or an earthquake. It could even be something truly far-fetched - an alien invasion, giant lizards or a wave of famished zombies.

KEY APOCALYPTIC NOVELS

Mary Shelley: The Last Man (1826)

MP Shiel: The Purple Cloud (1901)

HG Wells: The Shape of Things to Come (1933)

George R Stewart: Earth Abides (1949)

Richard Matheson: I Am Legend (1954)

But the explanation seems often to be man-made, misguided aggression or science gone wrong - accidentally released plague, nuclear war, or genetic modification gone awry.

This is one of Hollywood's favourite genres - the disaster movie. Look over the biggest grossing movies of recent years, and disaster movies are over-represented. Between them, Independence Day, I Am Legend and War of the Worlds took well over $2bn at the box office.

Within this category of disaster movies there is a a powerful sub-genre, the "post-apocalyptic fiction". Stories of a world having suffered, or in the last throes of, total collapse seem to have a perverse hold on the cinemagoer.

Deserted London

The modern incarnation of this genre has its roots in the febrile atmosphere of the 1950s, and perhaps its greatest pioneer was John Wyndham.

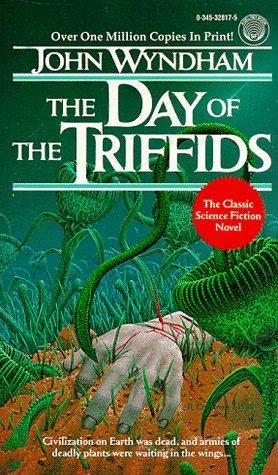

His 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids tells the story of a man, Bill Masen, who awakes in a hospital after treatment for temporary blindness caused by a sting from a genetically modified plant, a triffid.

The first 45 minutes of 28 Days Later are the first three chapters of The Day of the Triffids, marginally modified with the addition of zombies

Dr Barry Langford

Sensing he has been left unattended, he takes off his bandages to find the hospital is deserted. Upon leaving, Masen soon realises everybody has gone blind after witnessing spectacular lights in the sky the night before.

He, of course, was unable to watch the shower and has therefore retained his sight. The result of the epidemic of sightlessness is chaos and starvation, underpinned by a growing threat from the mysterious stinging triffids.

The tiny minority who have avoided blindness face difficult choices about how to continue their lives in a ravaged country, and how to deal with helpless blind survivors.

Its influence on some modern disaster films is apparent to any reader, says Dr Barry Langford, senior lecturer in film and television at Royal Holloway, University of London, and the author of the introduction to the Penguin Modern Classics version of Wyndham's novel.

"The first 45 minutes of 28 Days Later are the first three chapters of The Day of the Triffids, marginally modified with the addition of zombies."

Zombie lineage

Seeing a modern cinematic zombie lumbering unthinkably towards the hero or heroine as they try and make good their escape, it's not a massive leap to the triffids lumbering unthinkingly towards Bill Masen and Josella Playton, the resourceful heroine.

Armoured car in scene from 1981 adaption of The Day of The Triffids

Competing political views arise in the aftermath

Horrorphiles may trace the zombie lineage back to Richard Matheson's 1954 novel I Am Legend, but the triffids made their literary debut three years earlier.

Wyndham's work played with the paranoia of the Cold War then seeping into ordinary people's subconscious. In his novel, both the rise of the triffids (farmed for their oil) and the putative explanation for the blindness (an accidental release of chemical or biological weapons orbiting in satellites) are byproducts of the Cold War.

And the idea of malevolent plant life has a certain appeal now, in a time where some people are increasingly concerned about the idea of genetically modified organisms.

"The triffids are perhaps to us a more potent threat than even in Wyndham's time," Dr Langford suggests.

Rising seas

Andy Sawyer, librarian at the Science Fiction Foundation Collection at the University of Liverpool, concurs. "It has become relevant. There is a lot more anxiety about bio engineering now."

POLITICAL VISIONS IN THE NOVEL

Militaristic semi-feudalism

Polygamous pragmatism

Socialist idealism

Traditional morality

Apart from the triffids, Wyndham's other novels also cover topical issues. The Chrysalids tackles the idea of genetic mutation, possibly caused by nuclear war, and The Kraken Wakes tells of a world drowned by rising sea levels.

As well as meddling in nature, the relationship between cities and civilisation is a central theme in Wyndham's work.

At the heart of The Day of the Triffids is the idea that without cities there can be no civilisation. After everybody goes blind, the survivors cannot hope to sustain life in the cities. Pavements are soon cracked by weeds and streets overgrown.

"The empty city is a really powerful visual motif for the end of the world as we know it," says Dr Langford.

And in Wyndham's novel, the division of labour - and pampered lives - in modern society leaves people singularly ill-equipped where there is suddenly a battle for survival itself. One character rages that a group of women are unable to restart a generator.

Strange fantasy

"There is always a very strong sense of do we actually have the reserves to sustain ourselves? Have we become insufficiently robust?" says Dr Langford.

Wyndham's work provides a bridge from the work of HG Wells, Jules Verne and others, to the disaster and apocalypse fiction of today. It is as popular as it is today because it taps into a strange fantasy - a world in which we have avoided an all-embracing death and can do what we want.

APOCALYPSE THEMES

Science gone wrong

Ordinary man as hero

End of urban living

Need for old-fashioned skills

Competing political visions

"It's living on past the death of everything, living into a future that isn't mapped out and doesn't resemble anything we know," he says.

"When we die, everything ends, but in these stories that's inverted - everything ends but we get to live on. It is the world evacuated of everyone else. You can go into shops and have everything you want, live in any house you want."

And Wyndham's writing expounds an idea that is the template for many a modern film - the ordinary man, and ordinary woman, who have to take on a heroic mantle.

"He does follow that Wellsian tactic of making extraordinary things happen in ordinary circumstances. He saw himself as very much in the tradition of HG Wells rather than the American space opera," says Sawyer.

Wyndham also follows Wells in embedding an overtly political aspect in his science fiction. In the world that Bill Masen confronts, there are a number of different models for how to build society in the aftermath of the disaster.

Wyndham certainly did not invent disaster or post-apocalyptic fiction, and many of his ideas had precursors in earlier authors. But the way he expanded and expounded his ideas, and his popularisation of the nascent genre to a mainstream audience, make him an immense figure in science fiction.

No comments:

Post a Comment